FULL-ON SPOILER WARNING: I am going to discuss EVERYTHING that happens in this movie, right up until the last reveals. I’m writing under the assumption that you’ve seen this movie. You’ve been warned!

“Crimson Peak,” is a true gothic, and the gothic is a women’s genre. The protagonists are women, the most famous writers (Emily and Charlotte Bronte, Daphne du Maurier) are women. They are about old drafty houses (the traditional realm of women), marriage, and love.

Yet, gothics are about men. The men are the actors, the choosers, the authors of fate. After reading Wuthering Heights, the memory of Heathcliff lasts for years. Jane Eyre’s life is destroyed by Rochester’s first marriage. When she leaves the house, she is making an active out of a passive act–departing rather than merely refusing Rochester. But it is a change in Rochester which is ultimately necessary, not a change in Jane. And Max deWinter rules his nameless new wife.

“Crimson Peak” is NOT about men. It engages with the male-centric tropes of the gothic while re-casting the women as the actors and, ultimately, authors.

The best demonstration of this is poor Alan Cummings. He arrives more than halfway through the film, thinking he’s a rescuing hero. When he insists that he’s taking Edith away, takes out the newspaper article on the old Lady Sharpe, he’s playing out a story in his head, in which he’s the masculine savior and Thomas is the dark villain, Edith the damsel in distress. He doesn’t even pay attention to Lucille Sharpe, thinking that the only source of danger is Thomas.

He just didn’t get it: he’s walked into Lucille’s story, and this failure to understand almost kills him, and in fact turns him into a damsel whom Edith must rescue.

Thomas is the one who should be at the center of this story, but he is an extraordinarily passive character. Edith’s father identifies this right away when he tells Thomas, “you have the softest hands I’ve ever seen.” Thomas insists that, “my will is just as strong as yours,” but this is a complete lie. Thomas is a creature of reaction, not of action. He reacts to the empty clay mines by trying to build something better; he reacts to the lack of money by playing the part his sister wrote for him.

Thomas is not the author. He is a character in some else’s story, and he knows it. When he meets Edith in that first scene, he barely notices her, his attention instantly drawn to her novel on the table before him. His resistance to his sister began there, when he followed his attraction to Edith rather than the match his sister had already primed. When Edith later says that “characters change, they make choices,” he is struck, as if he had never considered that choice could change the story. He slowly builds up steam until he even burns the papers Edith had signed and “orders” his sister not to touch Edith again. But just because he has a bit of will at last doesn’t mean he has power, and he doesn’t even try to stop Lucille from murdering him. Even his ghost is transparent, insubstantial, blowing away on the wind.

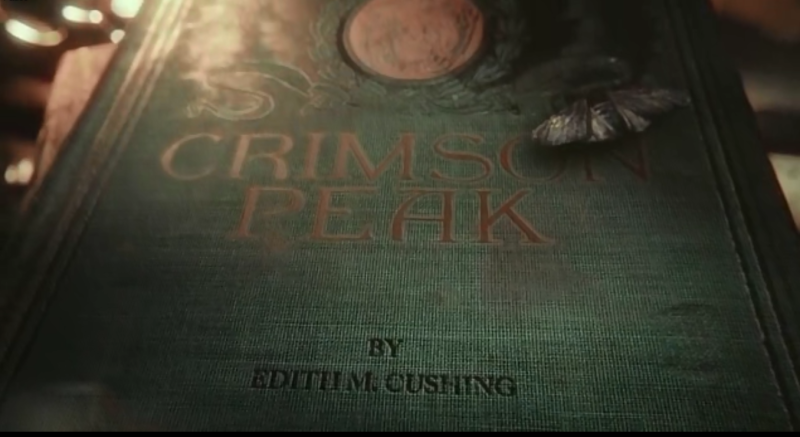

Crimson Peak is, at its heart, about the conflict between two authors: Lucille Sharpe and Edith Cushing. Lucille’s story is old, and she has been writing it for years in her generations-old house. Edith’s is young, just seeking publication, undergoing flux and constant revision. Lucille’s has given birth to ghosts, has swept up and destroyed lives. She can rewrite it, re-cast Edith and pretend the story won’t change. But those who threaten her story, like Edith’s father, she murders. Brutally.

Edith senses almost immediately that she is in someone else’s story. When women marry and move into their husband’s home, take his last name instead of their own, they become a part of his family, his story. But Edith isn’t content to merely accept this. When she sees a ghost, she follows it. She wanders through private areas of the house, steals keys, looks for the answers and never tries to pretend they aren’t true. Early on, she tells Thomas that she, “I don’t want to close my eyes. I want to keep them open.” Where others would flinch, she keeps going. And she never asks Thomas to save her, questions him only once after seeing her first ghosts, to which he answered evasively and with clear discomfort. Yet, Edith remains determined to know the whole of the story she has entered–because only then can she become one of its authors.

Lucille is the source of power in the Sharpe house. She murdered her mother (and perhaps her father too). With only one exception, she brews the tea meant to kill Edith. The ghosts of the Sharpe home may have been Thomas’s wives, but they are her victims. She belongs in the house, she is it’s madwoman in the attic. She is an incarnation of the depraved horror to which the ancient family has sunk: she has become both her mother, the source of the familial violence, and her father, the leg-breaker (she tells Edith that her father broke her mother’s leg only hours before she herself breaks Edith’s leg).

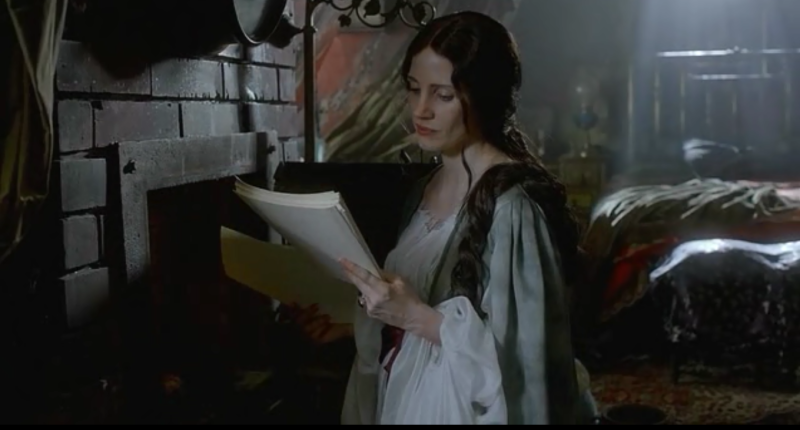

But Lucille’s story has a fatal flaw: she underestimates Edith. When she and Edith are in her room, Lucille insisting Edith sign the papers transferring her fortune to the Sharpes, Lucille thinks she’s won. But Thomas has already betrayed her, has already saved Alan rather than killing him–because Thomas is in love with Edith.

Lucille carelessly tosses Edith’s novel into the fire, mockingly saying, “you thought you were a writer.” But Edith has already re-written Lucille’s story. When she attacks Lucille, she does it with her pen. She escapes entirely on her own steam, and even had Thomas not already turned on Lucille, he would never have mustered enough strength to actually stop Edith. And her reaction to seeing Thomas is not to weep or beg for help, but to attack him and confront him with the truth he’s hidden from.

When Thomas tries to convince Lucille that, “we can be free,” can leave the house and its, “rotting walls,” behind, he is throwing in his lot with Edith’s story. It was Edith who first suggested they leave the house behind. And, because Thomas did ultimately love his sister, he tries to persuade her to see this new story through his eyes.

But when Lucille understands that Thomas has fallen in love with Edith, her story falls apart. At its center, Lucille’s story was of her and Thomas (while Edith’s was of herself). When he proves to have not only veered off script, but to in fact have betrayed the story, her reaction is to excise him, to destroy what Edith had created.

In the final scene, Lucille tells Edith, “either you kill me, or I kill you.” Both of the stories cannot exist together. And so Edith ends the Sharpe story, ends Lucille with one blow. She emerges from the darkness of the house into the light of the snowstorm, the only survivor of Lucille Sharpe.